In our last chapter on “WET code, DRY code, and Refactoring the low-level REST Adapter”, we refactored our code into a basic, yet reasonable low-level REST API adapter.

In this chapter, we’re going to cover proper Exception handling as well as creating our own custom Exceptions. Let’s start by looking back at our code, specifically our _do method.

Here are the ~30 lines we wrote last time:

import requests

import requests.packages

from typing import List, Dict

class RestAdapter:

def __init__(self, hostname: str, api_key: str = '', ver: str = 'v1', ssl_verify: bool = True):

self.url = f"https://{hostname}/{ver}"

self._api_key = api_key

self._ssl_verify = ssl_verify

if not ssl_verify:

# noinspection PyUnresolvedReferences

requests.packages.urllib3.disable_warnings()

def _do(self, http_method: str, endpoint: str, ep_params: Dict = None, data: Dict = None):

full_url = self.url + endpoint

headers = {'x-api-key': self._api_key}

response = requests.request(method=http_method, url=full_url, verify=self._ssl_verify,

headers=headers, params=ep_params, json=data)

data_out = response.json()

if response.status_code >= 200 and response.status_code <= 299: # OK

return data_out

raise Exception(data_out["message"])

def get(self, endpoint: str, ep_params: Dict = None) -> List[Dict]:

return self.do(http_method='GET', endpoint=endpoint, ep_params=ep_params)

def post(self, endpoint: str, ep_params: Dict = None, data: Dict = None):

return self.do(http_method='POST', endpoint=endpoint, ep_params=ep_params, data=data)

def delete(self, endpoint: str, ep_params: Dict = None, data: Dict = None):

return self.do(http_method='DELETE', endpoint=endpoint, ep_params=ep_params, data=data)Exceptions everywhere!

In case you weren’t aware, the requests.request method can raise an Exception. Specifically, requests.exceptions.RequestException — Let’s wrap that line with a try-except block:

try:

response = requests.request(method=http_method, url=full_url, verify=self._ssl_verify,

headers=headers, params=ep_params, json=data)

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

# do something here -- don't pass silently!Ok, we’re halfway there. The requests.request method is now contained in a try-except block and we’ve explicitly declared that we want to handle any RequestException type exceptions… But what do we do with this?

I’ll tell you what! We make a new exception for the TheCatApi library that we’re writing.

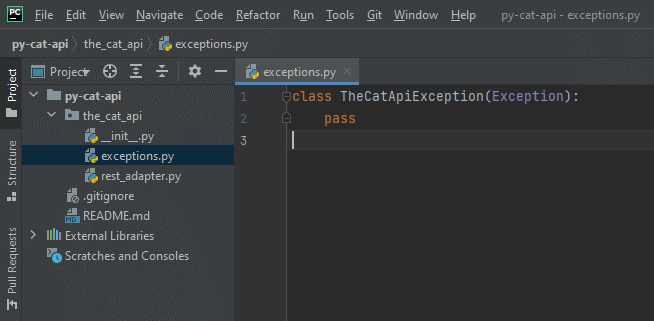

Right-click on the the_cat_api folder (the module) in the Project browser tree and Create a NEW Python file and call it: exceptions.py

Now add the following 2 lines to it:

class TheCatApiException(Exception):

passCongrats! You’ve just created your own custom exception unique to the_cat_api library.

Using TheCatApiException

Go back to the rest_adapter.py file and import this exception at the top of the file.

from the_cat_api.exceptions import TheCatApiExceptionAnd let’s add the final line to our try-except block:

try:

response = requests.request(method=http_method, url=full_url, verify=self._ssl_verify,

headers=headers, params=ep_params, json=data)

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

raise TheCatApiException("Request failed") from eWhat have we done here? By raising our own custom exception, TheCatApiException, we’re indicating to any program that consumes our adapter where the failure happened. Also, note the as e and the from e.

Catching the Request exception as e is a common technique to capture the Exception in a variable when it happens. We’re taking the message from the exception, e, stuffing the message into TheCatApiException and then using from e when raise-ing, we’re continuing the stack trace. If we hadn’t used from e after raise-ing, then the stack trace would have been disrupted. Keeping the stack trace intact is important later if you’re ever debugging a program and trying to figure out where in the stack a failure happened.

This leads us to further enhancing our rest adapter with a custom Response model and Logging in the next chapter… Step 5: Creating a new Response Model

Source code: https://github.com/PretzelLogix/py-cat-api/tree/04_exception_handling

5 replies on “Step 4: Exception handling and Raising new custom Exceptions”

[…] This leads us to the next topic of Exception handling and Raising our own exceptions in the next chapter… Step 4: Exception Handling and Raising New Exceptions […]

[…] our last chapter, we talked about properly catching exceptions and re-raising with a custom exception in our _do […]

[…] Step 4: Implement Exception handling and raise new custom Exceptions […]

Hello, I know it’s been a few years since you wrote that but I just stumble upon it.

First great job! Explains me a lot. A few comments/questions parts up to this point:

1-I made my adapter an requests.Session subclass. Although I overwrite it’s verb methods, it let’s me set the header only once and use it afterward. That’s just another way to do the same thing actually.

2-making the requests:

a) requests.Response has the method “raise_for_status”. Do you see a downside of using it vs your status test?

b) I, personnaly, would raise both status error and the other exception at the “same time” (ie, I made a _make_request method). Again, I think this is preference but do you see any counter-indication for that?

Thanks for the comment. I’m always glad to talk about this guide. It’s supposed to be both practical and educational.

1. Making your REST Adapter a subclass of requests.Session is definitely something you should reconsider. As you get deeper into Python and programming in general, you’ll find that things aren’t as clear-cut as we would like them to be. Even the “Zen of Python” is mostly just a list of suggestions to think about and ponder (and not a list of hard-and-fast rules.) As to why you should probably reconsider sub-classing `requests.Session`, there is a philosophy in programming known as “Favor Composition over Inheritance”. You can read more about it here: https://python-patterns.guide/gang-of-four/composition-over-inheritance/

How do we refactor your REST Adapter class to use `composition` (instead of inheritance)? Without getting too much into it, you can create a `self._session` private variable in your `__init__` method and assign a `Session` object to it. (I have been thinking about writing a 16th chapter to this guide where I cover this exact topic because I can’t fit it all into a brief comment here. It really deserves its own full page to cover it properly.)

2. As for `raise_for_status()` method, I don’t know why my co-worker and I have habitually avoided it. The method has been a part of `requests` for a very long time; it’s not like it is new. Again, I think it comes down to philosophy. Personally, I try to avoid raising/causing exceptions when it is not necessary. The reality is that HTTP errors aren’t particularly exceptional. They’re quite common, in fact, so using a method to intentionally raise an exception when nothing exceptional is happening seems silly to me.

There are other reasons for avoiding exceptions. In some languages (like Java, C#, C++, and others), raising an Exception causes a significant performance penalty. From my understanding, this is not the case for Python (ie. very minor performance penalty), but still there is a philosophy about not “using exceptions for flow control”. Personally, I would rather proactively check existing status values, rather than have to handle exceptions and figure out if I can recover from the exception. (“Ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”?) Some folks might go as far as to say that “using exceptions as flow control” is an anti-pattern, but I’m not sure it is.

Anyway, I’ll have to think about this more and chat with some of my peers about this. Thanks for bringing this up. It’s a good question.